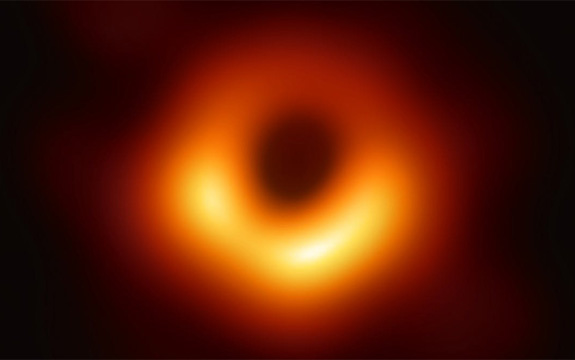

All the light in this region is heading toward the event horizon, and we don’t see it because it makes it there. Light that travels beyond the photon orbit could, conceivably, escape the black hole if something was to reflect it back. That boundary is known as the photon orbit, and its diameter is about 2.5 times larger than that of the event horizon. You might think this ring of material, or the innermost edge of it, represents that event horizon. (You’ll see it’s brighter on the bottom than on the top). In the image, look at the ring surrounding the dark center. Second, think about what’s happening to the light we can see Those fishes have left our observable universe. When you look at the dark region of the black hole, know: There’s light and matter in there. “When the matter and light get too close to the black hole, the black hole just swallows it up, it removes that light from the universe,” Mack says. In this metaphor, the beam of light is the fish - and it’s approaching the black hole. At a certain point, the water is rushing so fast that the fish can’t escape by swimming in the other direction. Now imagine a fish swimming toward the top of the waterfall. That region, called the event horizon, is kind of like the top of a waterfall. That single point has such strong gravity, that as light approaches it, there’s a region beyond which nothing can escape its grasp. The black hole is black because of a singularity, or a region where the fabric of space and time itself has collapsed in on itself, forming a single point with infinite density.

There’s light in that dark spot, but we can’t see it. The dark spot is a shadow, a sink, an exit portal from our observable universe. The first thing to know is that while it may look like an object, it isn’t one - not exactly. Let’s begin with the dark spot, the hole in the center.

First, check out the singularity, and the light we can’t see Two astrophysicists - Sheperd Doeleman, the project leader of the Event Horizon Telescope, and Katie Mack of North Carolina State University, who was not involved with the effort - walked me through a few of the coolest aspects of the image that helped me appreciate just wonderfully mind-blowing it is.

But there’s so much more to it than what immediately meets the eye. Some may not be impressed by the slight blurriness of the image. The image they created has been eagerly anticipated by all those enthralled by black holes, and it does not disappoint: a deep black well in the center of a bright ring of plasma and gas. The image comes to us from a vast and incredibly sophisticated scientific collaboration called the Event Horizon Telescope, which involves 200 scientists in 20 countries who’ve been working together for nearly a decade. That's bad news, because Myoshi thinks the alleged error could affect the way other black hole images turn out - including, provocatively, the new EHT image of the black hole at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy released this month.This week, a group of scientists unveiled the first-ever image of a black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy, some 55 million light-years away.

National Astronomical Observatory of Japan researcher Makato Myoshi and colleagues used a wider field of view to get the new image of M87*, which cut out the ring of light around the donut-shaped structure that appeared in the 2019 image. As with any algorithm, though, that unfortunately means there's room for human error and incorrect assumptions - and that's an issue here, because the new image doesn't look like the one from 2019. Like the original team, they used an algorithm to fill in the blanks and compile the vast heap of data into a single image. New Scientist reported this week that the group used the same data from the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a collection of eight radio telescopes that act as one, to produce a new version of the iconic black hole image released in 2019. It took researchers in Japan three years to produce an image of M87*, the black hole in the center of the M87 galaxy. Sorta TwinningĪ new image of a black hole in the center of a distant galaxy just dropped, but it's making researchers worried that the first image of the same one wasn't quite right. The last image was a "mistake," they say.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)